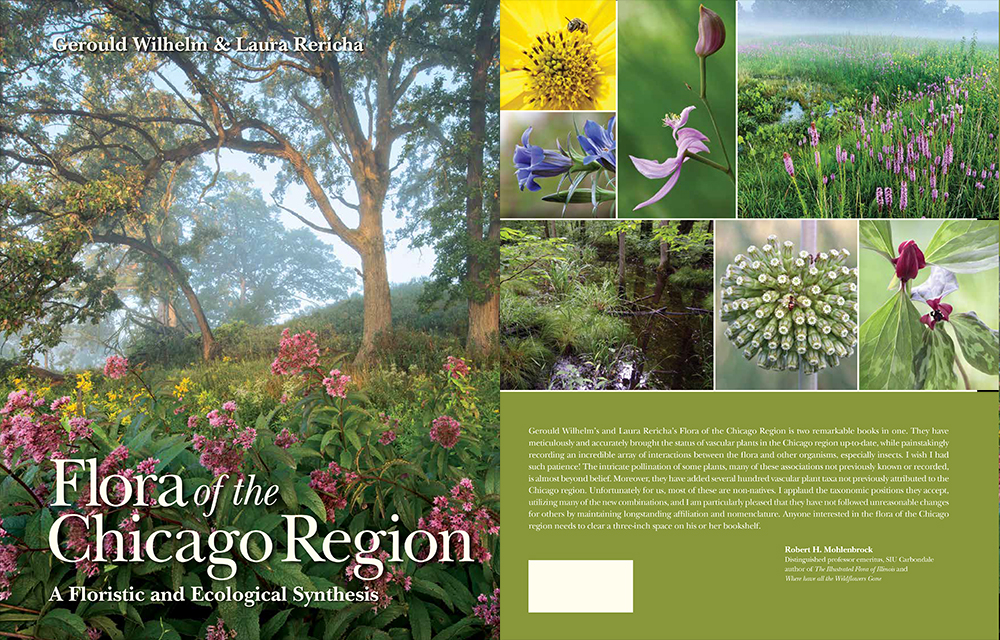

Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis

After 15 years and close to 100,000 hours of work, the book is finished. We think it's everything you were hoping it would be —thoroughly researched, detailed, extensively illustrated.

Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis is available for purchase at indianaacademyofscience.org. The book is also available at the Morton Arboretum bookstore in Lisle, Illinois

Flora Of the Chicago Region: Updated Glossary

Sample Readings and Artwork from Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis

Reviews

News

May 17, 2019 The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries announced that Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis has been awarded the ANNUAL LITERATURE AWARD OF EXCELLENCE in the category of Botany and Floras. Check out CBHL's website at cbhl.net.January 23, 2018 Dr. Gerould Wilhelm and Mike MacDonald were interviewed on WBEZ's Worldview

April 5, 2018 Laura Rericha and Dr. Gerould Wilhelm were interviewed on Chicago Tonight

April 11, 2018 Laura Rericha and Eileen Figel were interviewed on WBEZ's Worldview

This book is the latest publication in a long tradition of research and documentation of the plants of the Chicago area. Following is Dr. Wilhelm's historical perspective on earlier editions.

The first edition of Plants of the Chicago Region was published in 1969 by Floyd Swink. At that time, Floyd was the taxonomist at the Morton Arboretum and a naturalist, much beloved by all in the region who had an interest in plants, birds, insects, and even local history. In this flora, he had catalogued all of the vascular plant species that were known from the region at that time. This was a much expanded and annotated version of "The Lamp List", which he had compiled at the request of Dr. Herbert Lamp, of Northeastern Illinois University, during the middle 1960's.

At that time, there were several books available to Chicago area plant enthusiasts and naturalists, but they all had different nomenclature, and some included areas as large as the northeastern United States. H. S. Pepoon's flora, published in 1927, was useful, but included only the immediate purlieus of the City of Chicago. Peattie's flora, published in 1930, was limited to the dune area. Charles Deam's flora, published in 1940, was magnificent, but included only the Indiana counties. The 2nd edition of George N. Jones's flora, available by 1950, included only the Illinois counties. Knowledge of Wisconsin was scattered in the botanical journals, neither compiled nor readily available. Edward Voss was working assiduously on the Michigan flora, but the first of three volumes, the monocots, would not appear until 1972. Henry Allen Gleason's, New Britton and Brown, had been available for a decade or so, and it was illustrated, but it included all of the plants known in the northeastern United States at the time. Merritt Lyndon Fernald's Eighth Edition of Gray's Manual, 1950, also included all the northeastern states, but its presentation was generally too recondite for the weekend botanist.

In 1953, Floyd had published A Guide to the Wild Flowering Plants of the Chicago Region, but it, too, had its limitations. Always trying to teach and to accommodate, tutored by the famed botanists, Charles C. Deam and Julian A. Steyermark, Floyd produced his compilation in 1969. In point of fact, few states or regions of the United States even had floras; Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Ohio, Tennessee, Wisconsin, to name a few, all lacked a disciplined accounting of vascular plants.

Taking Floyd's data, and following his format, Raymond F. Schulenberg wrote the body of the text. Ray's knowledge of the flora was so intimate and reflective of deep wisdom as to render him virtually alone among botanists of his day, or today, or any other day. Both were my mentors.

They produced a book unlike any other in the history of local floras. Rather than present the plants in a traditional but esoteric "phylogenetic order," Floyd listed them alphabetically. He reasoned that the user of the book was certain to know the alphabet and was interested in the associated plant communities and specific habitats of local plants; he knew they were not interested in becoming sharpened on the latest phylogenetic theories or arrangements based upon them. They listed the regularly associated vascular plant species for each plant and correlated the nomenclature, which was Fernaldian, to all of the other available references and keys. He did not list the nomenclatural authority for each species because he knew that the checklist user was unconcerned with and did not need additional abstract abbreviations to distract from their real interests.

He reasoned that he had not examined the type specimens so would be unable to declare that the plant in hand was really the plant understood to be the one designated by the naming authority. What he did know was that the plant in hand keyed to such and such a name in Fernald's 8th edition, Pepoon's flora, Jones' flora, etc. He was a stickler for orthographic correctness. A little over 2000 plants were listed.

The checklist's emphasis on a plant's associates, local distribution, and a devotion to the names in Fernald's 8th edition, along with the book's encyclopedic arrangement and the "leaving off" the authorities made Floyd a pioneer among floristicians—and an annoyance to doctrinaire botanists of the time. The pusillanimity of most academic botanists, I noticed as a young man, was disappointing. Only a few of the botanists of stature at the time, including Drs. William Beecher, William Berger, Robert Mohlenbrock, Paul Sorensen, Julian Steyermark, John Thieret, Edward Voss, Richard Wunderlin, and a few others were openly appreciative of Floyd's efforts. This meant a lot to Floyd, and gave him the necessary approbation to carry him through thick and thin, throughout his career.

Each species was accompanied by a map of the 22-county region that detailed each plant's known distribution in 3 southeastern Wisconsin Counties, 11 in northeastern Illinois, 7 in northwestern Indiana, and 1 in southwestern Michigan. This region was chosen because at least half of the area of the counties included lay within a 65-mile radius of State and Madison, in downtown Chicago. Floyd and others regarded this geographic area to be within the reasonable reach of a day-trip by Chicago plant enthusiasts and naturalists.

Plants of the Chicago Region was published by the Morton Arboretum right at the time the people of our country were becoming aware of the environment. The book's appearance coincided with the National Environmental Policy act of 1969. Typed copy-ready on a manual typewriter by Floyd, virtually error-free, all 250 copies of the print run were purchased quickly by a public ever more interested in understanding the Chicago region landscape; it was a soft-bound book. While a few local patrons excoriated Floyd for having "failed" to map Anemonella thalictroides from Grundy County, as an example, most others were inspired to seek out new habitat locations and report them to Floyd.

In so doing, we gained an ever increasing knowledge and understanding of where our remnant landscapes still endured—and in what condition they languished or flourished. Plants were no longer elements of a laundry list of value-neutral data. Students of the flora began to see each species as able to tell a story about the place where it grew, which enfranchised the plants and their places to people like no other format had ever done.

With the help of Chicago's floristic patrons and naturalists, Floyd, in 1974, was able to produce a 2nd edition that sustained the innovations of the first and added much new information on local species; 1000 copies were printed. It seemed improbably optimistic that there would be 1000 people who would buy a book that had no pictures and consisted of lists and more lists of Latin names. He listed appreciatively all the people who had contributed new information. It also was typed copy-ready on a manual typewriter, but reduced in size to make a smaller paper-bound book. These volumes, too, were all soon in the hands of grateful students of the flora.

Having just arrived at the Morton Arboretum in February of 1974, my role in this edition of the catalogue was to put the distribution maps together. Ray Schulenberg and I had made a significant effort over the growing season of that year to voucher many of the "sight records" that were embedded in the distribution maps of the first edition. This book, with rare exceptions, continued to follow the nomenclature presented in the first edition. Even though there had been numerous "name changes," since 1950, Floyd reasoned that his patrons were more interested in continuing to learn the habitats of local plants, and did not need to be confused by "updating" the nomenclature. It recognized 2216 taxa.

Five years later, after much new information had been accumulated, I collaborated more intimately with Floyd to produce yet a third edition. This one preserved the substance and innovations of earlier editions, but added a glossary, bibliography, and identification keys to each genus, species, and subspecific taxon. The distribution maps codified as to whether or not we had seen a specimen from the county, or if the record was based wholly on a literature report. An open circle represented a "sight record." In order that the user of the book might relate deeply to the discrimination of native versus non-native plants, I had Floyd render each adventive species in light italics, so that they would appear visually distinct in associate lists. Floyd did this readily, even though he had to change the typing element in the new IBM Selectric typewriter every time a non-native species appeared in the text. He was able to accomplish this with great alacrity because he was, literally, a world-champion typist. This 3rd edition veered little from Fernaldian nomenclature, but it did include the nomenclatural authorities, not because it added taxonomic validity to do so or to placate critics, but because the book was becoming less of a checklist and more of an encyclopedic source of information for local plants.

In 1977, I had published a methodology for the evaluation of the floristic quality of vegetated landscapes, with the focus on Kane County, Illinois. It was described in more detail and presented with "coefficients of conservatism" for all the native plants of the Chicago region. For the first time, students of a flora had a practical, dispassionate, and repeatable metric that could be applied in the qualitative evaluation of remnant landscapes. As with Floyd's effort, this evaluation system received fairly intense criticism, particularly from trained ecologists, but many applied users found value in it. This 3rd edition listed 2,241 recognized taxa.

The compendium of contributing patrons continued to grow. Plants of the Chicago Region, again a soft-bound volume, continued to break new ground.

There was a 4-year hiatus from September 1980 to May 1984, during which I pursued an advanced degree in Botany from Southern Illinois University, stewarded there by Robert H. Mohlenbrock, who was one of the few professors in the country who encouraged students to do floristic work in pursuit of a Ph.D. My dissertation was on the vascular flora of the Pensacola, Florida, area, but my now lifelong study has been the flora of the Chicago region, having attached myself to Floyd Swink, as well as Ray Schulenberg, during my sojourn at the Morton Arboretum.

After fifteen years of use, this 3rd edition, which numbered 2000 copies, was long out of print and a new generation of users lobbied for an update. Many in the academic world believed that the Chicago region flora was "done", and that we should move on to more "original" research. Under pressure from our supervisors to spend no more time on the effort, Floyd and I, still at the Morton Arboretum, nevertheless worked together to accommodate a throng of local botanists with yet another edition. In 1994, Bill N. McKnight, of the Indiana Academy of Sciences, who understood that it was not done, sponsored the production of the now widely acclaimed 4th edition. It included all of the features of the previous editions, but provided much more, including a refined methodology for floristic quality assessments, an illustrated glossary, an index to synonyms and misapplied taxa, and several sections that detailed the phytogeography and authorship of local plants. Floyd, with the help of Linda Masters, typed this edition using a computer, creating a copy-ready draft in Word Perfect. Linda can testify to the adjustment Floyd had to make, his life up until then having been as a master of the manual typewriter. This hard-bound, jacketed volume presented 2,530 mapped taxa. All were sold by the end of 2001, but by then Plants of the Chicago Region had become a required reference to anyone interested in local botany and ecology. Many far outside the region now found the book to be indispensable.

Because it was becoming too untenable to sustain Fernald's nomenclature religiously, and because our serious audience had become more wide-reaching, we made some name changes—which drew some fire from some of our time-honored patrons. The chief criterion was when a name was patently and inarguably inappropriate. An example of such a change was the splitting of Gerardia into three other genera: Agalinis, Aureolaria, and Tomanthera. Gerardia was a name already in use in the Acanthaceae, so it was completely unavailable for plants in the Scrophulariaceae. Nevertheless, our empathy still lay with the local user whose interest was in the ecology of the plants and not their nomenclature. We did not utilize options such as changing Petalostemum to Dalea, or Andropogon scoparius to Schizachyium scoparium—although politically, it would have made life more comfortable. 5300 copies of the 4th edition were printed, of which 40% were sold prior to publication! In fall, 2007, an additional 1200 copies were printed by the Indiana Academy of Science in an attempt to fill the gap until a newer revision could be written. Half of these were gone within a year—most potential users not yet aware that it is available, at the academy's usual minimal price.

By now the concept of species conservatism and floristic quality assessment had become widely used and much appreciated as a tool by many practitioners of restoration land management. Also, the concept and role of non-native species had become a well-known consideration in evaluating contemporary landscapes. Many are not even aware that, prior to Ray Schulenberg's philosophical comprehensions of the tensions between native and adventive species, non-native species were regarded as merely "naturalized" floristic elements to which ecologists attributed value-neutral considerations with respect to their presence in a landscape.

Interestingly enough, the Chicago region has produced a disproportionate number of innovators in the area of ecological and botanical thought: Henry C. Cowles ["father of ecology"], Jens Jensen [naturalistic landscape design], May T. Watts [interpretation to the public], Dwight H. Perkins [educator and forest preserve visionary] Julian A. Steyermark [student-oriented floristic work], Floyd A. Swink [empathy for the naturalist user], George Fell [nature preserves] Ray F. Schulenberg [prairie restoration], Robert F. Betz [discovery and preservation of remnant prairies], Stephen Packard [organized volunteer land stewards], and Douglas Ladd [holistic comprehension of landscape systems], among others. If one moves a few miles to the north, we must include John Muir [ontogeny of national parks], Aldo Leopold [land ethic], and John T. Curtis [concept of vegetation descriptions]. All of these people believed that our relationship with our landscape transcended the doctrines of their day and were more important than the comfort zones of contemporary colleagues.

There is something about the obvious interface between one of the great metropolitan regions of the world and the still-remaining remnants of the prairies, forests, fens and bogs that have driven our people to come better to understand both our landscape and our cultural relationship with it. Even a small fraction of the millions of people interested in natural history has added up to a critical mass that produces uncommon understandings and perceptions. All of these practitioners and observers have been embedded in a relatively large community of naturalists and people deeply interested in the health and wellbeing of our planet, and in many ways authentically connected to this place.

This interest has expressed itself in the Kennicott Club, which used to meet regularly at the Field Museum and the Chicago Academy of Sciences; Floyd Swink was an active member. By 1990, homeowners interested in native landscapes had organized, through Lori Otto, of Milwaukee, the now nationally popular, "Wild Ones." Not long afterwards, more than 30 Chicago Area organizations and institutions banded together to form "Chicago Wilderness," a collaborative vision of conservation unlike anything that the world has known. Today, more than 230 public and private organizations are working together to protect, restore, study and manage the natural ecosystems of the Chicago region.

In 1996, I left the Morton Arboretum and went into private consulting. Floyd passed away in 2000. I was quite certain that the curtain had fallen on my involvement in Plants of the Chicago Region—although, I knew just as certainly that much more was to be "done." Meanwhile, Laura Rericha, a young naturalist with the Forest Preserve District of Cook County, had been studying with Floyd for the last five years of his life, nearly day and night, on the insects, particularly those that they observed to interact with our vascular plants.

Laura at least as brilliant as Floyd—by his own account—is an ornithological phenomenon. Floyd would attempt to explain her genius to others, including me, but the truth of it was too incredible to comprehend. Dwight Perkins, as a believer in the forest preserves and local parks, would be proud of her contributions to our knowledge of public lands—even as her supervisors within the Forest Preserve District are today.

Shortly after Floyd had passed, Laura and I met at a meeting at the Cook County Forest Preserve at Camp Sagawau. Given her already unprecedented knowledge of birds, insects, and plants, I was inspired to engage her in the writing of a "5th edition of the book," in order to provide our patrons with the observations she and Floyd had made on this whole new guild of species that associated with our plants. Her enthusiasm for such an effort was in such consilience that the idea was virtually mutual.

Initially, we believed that we would collaborate on a 5th edition of Plants of the Chicago Region, and proceeded for the first couple of years on that basis. As we began to format the book and organize the content, it became quite clear that it was going to be notably different from Plants of the Chicago Region. As it is, the 4th edition was quite dissimilar from the first annotated checklist, but each iterative edition, with Floyd as the senior author, was sufficiently linked to retain the title and the general format.

With this impending volume, however, it became evident that there were significant reasons to change the title, and, of course the authorship. All of the information of the 4th edition was retained and updated, but the Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis was to contain new features that would make it a truly unusual floristic work. These features include:

- A least 1 original illustration for each of the 900 genera.

- Morphological descriptions for each family, genus, and mapped taxon.

- The etymology of generic, specific, and subspecific names are provided.

- Significant re-evaluations of many problematic genera, including Amelanchier, Apocynum, Chenopodium, Crataegus, Echinochloa, Mentha, Panicum, Rosa, Rubus, Salix, and Vernonia

- Addition of a whole new section of associates that account for all the insects, birds, and mammals that we have seen to have intimate relationships with our vascular plants: nectaring of extrafloral nectaries, collection of pollen, seed or fruit utilization, myrmecochory, gall formation, and fungal infections.

- Where vascular plants, or their communities have characteristic associations with bryophytes, hepatophytes, and lichens, these cryptogams are mentioned.

- For many flowers, the synchrony among male and female phases of the flowers is discussed in conjunction with visiting insects.

- Nomenclatural alignments, still conservative, are much more "current" than any of the other editions, and such changes are much less likely to annoy future users, since the older floras—Deam, Fernald, and Jones are far less in use. About 95% of the names align with those in the USDA Plants on line.

- Coefficients of conservatism have been re-evaluated for all the native species, including the 244 presented as new to the flora since 1994.

- Ten plants new to science since 1994, including Hypericum swinkianum described by the authors, are presented.

- The plant community descriptions are much more fine-grained than in previous editions and more closely described in conjunction with local natural divisions and surface geology.

The synthesis of other organisms, plant and animal, that are interlinked with our plant species is heretofore unknown among floristic works of this scale. The research for and production of this flora could not have been done without the coterie of donors who believed in the authors and provided pecuniary support for the effort. It may be the first time that a floristic effort of this scale has been made possible through private support.